The long-term outlook for the Reef will depend on decisions and actions taken at a global level to address climate change, and on effective management of threats to the Region’s values. The threats are multiple, cumulative, and intensifying, so management approaches must be constantly evolving and agile (Box 10.1). The urgency of responding to threats currently facing the Reef, combined with the limited time and resources available, compels management to identify, prioritise and safeguard key species, habitats or processes that will enhance the resilience of the Reef ecosystem, including potential climate refugia.2160 Finding more effective ways to plan for, and respond to, changing environmental and social conditions is essential.

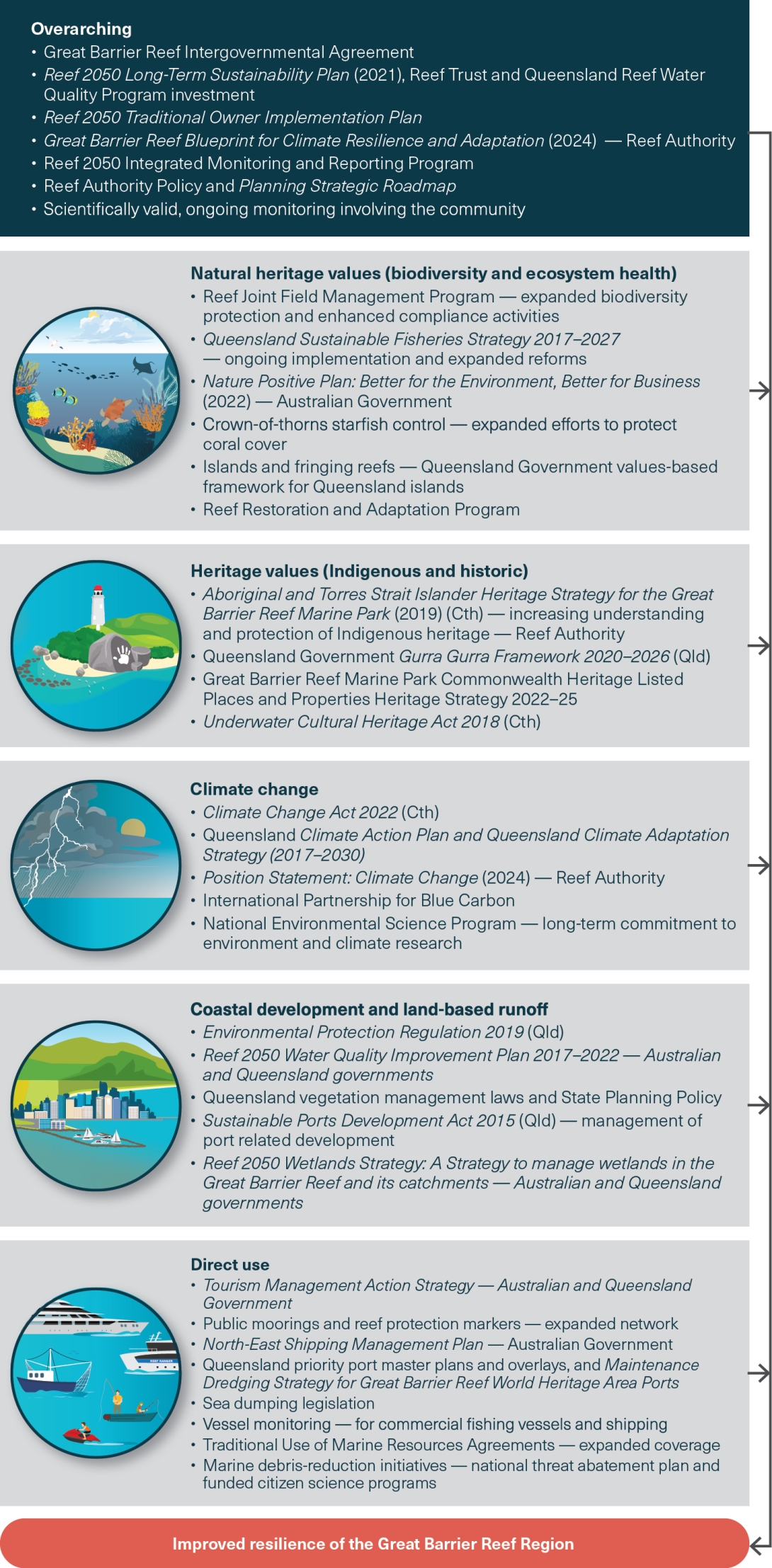

This assessment of the long-term outlook for the Region’s ecosystem and its heritage value includes consideration of current management arrangements and relevant management initiatives identified but not yet fully implemented (Figure 10.4). The future initiatives under the Reef 2050 Plan, the Great Barrier Reef Blueprint for Climate Resilience and Adaptation 1984 (Blueprint 2030), and the Reef 2050 Water Quality Improvement Plan 1883 and Reef 2050 Traditional Owner Implementation Plan 1120 set the framework for improving resilience-based management and protection of values. Also considered are the future commitments of the Australian and Queensland governments and partners under the Reef 2050 Plan.

Significant management initiatives continue to protect values and support resilience of the Region. Despite this, and the documented recovery of some key habitats and species (Chapter 8), overall resilience is being challenged. The scientific evidence is clear: the most urgent initiatives are those that will halt and reverse climate change and those that will effectively improve water quality at the regional scale. International forums, national and state energy transition agendas, and partnerships at all levels provide opportunity for advocacy and encouragement around transformative actions for emissions reduction.1984 Further improvements in water quality, protecting and restoring supporting coastal habitats, and reducing fishing pressure on certain fish stocks will support the resilience of the Reef ecosystem in the face of climate change threats. In addition, recent evidence confirms that controlling crown-of-thorns starfish populations represents an essential management tool for enhancing Reef resilience.