The south-west Pacific population of loggerhead turtles nest on the Region’s mainland and island beaches. The primary nesting sites for this stock are from Mon Repos near Bundaberg (outside and just south of the Region) to Wreck Rock (inside the Region). Key nesting sites within the Region include Wreck, Erskine and Tryon islands and the southern Reef. Post-hatchling loggerhead turtles disperse to oceanic pelagic foraging areas off Chile, Peru and Ecuador via the East Australian Current and the South Pacific Gyre.2106, 2107 They remain in oceanic waters for approximately 16 years, returning to recruit to benthic foraging areas in continental shelf waters in the south-west Pacific as juveniles.2108

The population has been affected by several historical, ongoing and recently emerging pressures. From the 1970s to the year 2001, bycatch mortality in the Northern Prawn Fishery, Torres Strait Prawn Fishery and Queensland East Coast Otter Trawl Fishery contributed to the population’s severe decline of 86 per cent during that period in northern and eastern Australia.2109,2110 The use of turtle excluder devices was made mandatory in the otter trawl fisheries of northern Australia in the early 2000s. This reduced the incidental capture and mortality of subadult and adult loggerhead turtles. A recent study reported that most loggerhead turtles returning to Wreck Rock beaches in the 2022–23 breeding season had breeding histories spanning less than 20 years.471 This indicates they commenced their breeding life following the mandating of turtle excluder device use.

Predation of loggerhead nests by foxes, dogs and goannas on the mainland has led to significant loss of clutches since the 1970s. Predation by goannas and foxes is still recorded at Wreck Rock.471 The draining of the swamp behind Mon Repos beach in the 1960s and 1970s lowered the water table, contributing to low hatching success in hot and dry conditions. Hatching success is poor at mainland nesting beaches due to natural erosion, storm erosion and flooding.471,2111 Erosion is increasingly evident as extreme weather events become more frequent. Entanglement in fishing gear and recreational boat-strike are identified as high-risk threats for loggerhead turtles.444 Ingestion of marine debris, particularly ingestion of plastic by small post-hatchlings who feed at the surface, is increasingly reported.2112

Climate change is also affecting loggerhead turtles in the Region. Much like other marine turtle species in the Region, hatchling sex ratios for loggerhead hatchlings are changing due to increased sand temperatures affecting their temperature-dependent sex determination.443 Extreme weather events are expected to increasingly cause erosion and loss of nesting sites.2113 Furthermore, altered sand budgets, rising sea levels, changes in forage communities, ocean acidification and shifts in prevailing ocean currents are emerging threats that are poorly understood and are likely to be beyond the influence of local management efforts.443

As sea temperatures continue to affect sex ratios of turtles, male sea turtles may become increasingly rare due more females being produced at warmer temperatures.443,2114 However, there is strong evidence that males generally breed more frequently than females, and that individual breeding males actively search for females and may mate with multiple females from different nesting sites.2114 These characteristics can help mitigate female-biased hatchling sex ratios, conferring a degree of resilience against warming in the short term.

Management

Loggerhead turtles are listed as endangered in Australia under both Commonwealth (EPBC Act) and Queensland (Nature Conservation Act 1992) legislation. Loggerhead turtles are protected under the CITES convention as they are listed in Appendix 1, species threatened with extinction. A single species action plan 2115 has been prepared to guide regional management of the South Pacific Ocean stock of loggerhead turtles under the Convention on Migratory Species (Bonn Convention), to which Australia is a signatory. Additionally, 80 per cent of loggerhead turtle nesting occurs adjacent to the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park within the Queensland National Park estate, which is managed by the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service under the Nature Conservation Act 1992. Management of loggerhead turtles and their habitat within these areas is conducted by Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, the Reef Authority, local government councils, the Indigenous Land and Sea Ranger Program and community volunteers.

The Queensland Turtle Conservation Project is one of the world’s longest running research and monitoring programs, having collected loggerhead turtle nesting data since 1968. The Queensland Marine Turtle Conservation Strategy 2021–2031,443 and the Recovery Plan for Marine Turtles in Australia 2017–2027 1351 outline key threats to marine turtles in the Region and management objectives to support recovery of their populations. Understanding and responding to impacts on marine turtles are also goals of the Reef 2050 Plan.2116 Recent targeted initiatives to support loggerhead turtles include plans to re-establish the swamp behind Mon Repos to improve water flow to the nesting beach, led by Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service. The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water’s National Light Pollution Guidelines for Wildlife 2117 outlines recommendations to address potential adverse effects of artificial light on marine turtles. Public awareness campaigns along the Woongarra coast promote reducing artificial light during the nesting season to help mitigate disorientation in female turtles and hatchlings and increase recruitment success.2118

Beach cooling trials along the Woongarra coast nesting beaches commenced in the 2021–22 nesting season. The success of interventions, placing nests in shaded incubation cages and hatcheries or applying artificial rain to in situ nests, is yet to be evaluated.470

Funding has also been provided through the Nest to Ocean Turtle Protection Program as projects funded aim to reduce the threat of predation on marine turtle nests and hatchling (including loggerhead turtles).2119

Evidence for recovery or decline

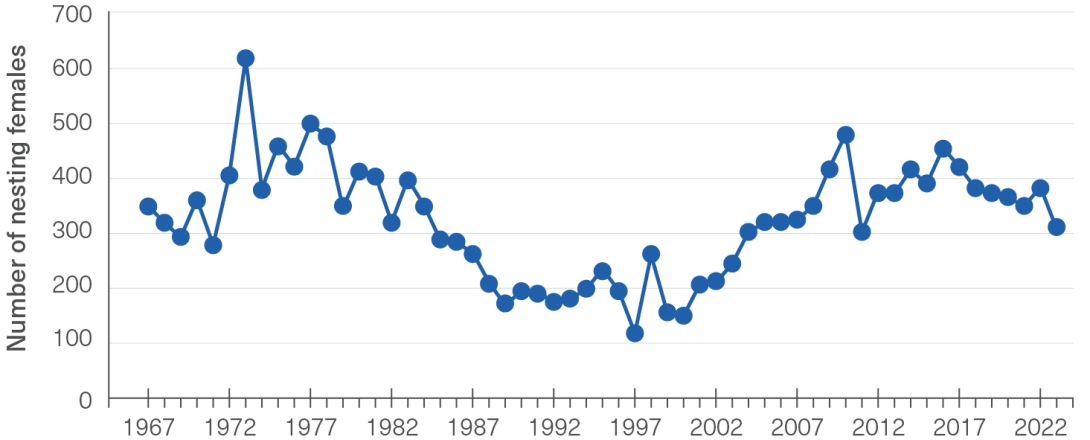

Populations of nesting females are declining on both the mainland and islands. Along the Woongarra coast, numbers of nesting female loggerheads decreased from 497 in 1977–78 to 207 in 2001–02 (Figure 8.7). From 2001, mainland nesters began showing initial recovery in numbers 471,2120 following the introduction of mandatory turtle excluder devices in the Northern Prawn Fishery, the Torres Strait Prawn Fishery and the East Coast Otter Trawl Fishery.

Figure 8.7

Number of tagged loggerhead turtles nesting, Woongarra coast, 1967 to 2023

Data for the 1967 and 1968 nesting seasons are population estimates. Data for nesting seasons from 1969 to 2023 are derived from population censuses. Nesting seasons occur over summer and are referred to by the year in which they start. Source: Queensland Department of Environment and Science (2023)438 and Limpus (2008)2108

The number of females nesting on the Woongarra coast had increased to 385 in 2022–23, but the 2023–24 the figure is lower (Figure 8.7).438 Further north along the mainland coast, numbers at Wreck Rock beaches also recovered somewhat after 2001, but they are showing signs of decline over the 6 years leading up to 2023–24.471 The recent downturn in the size of the annual nesting population of loggerhead turtles is of concern.

In the 1970s, island beaches hosted most loggerhead nesting in the Region, but more recent numbers nesting on island beaches are very low. Negligible recovery has been observed at the island rookeries in the Region, 58 females were recorded nesting at Wreck Island in 2022 compared to 57 in 2001. These numbers are significantly lower than the 589 recorded in 1977.438 The difference in recovery between island and mainland nesters is attributed to their different foraging distributions.467 Island nesters typically migrate further, and northward, to their foraging grounds. This movement means they are more likely to traverse unprotected habitats in international waters, where they are susceptible to harm during migration and foraging.467

Recruitment of young turtles has declined by half over the last 20 years

Recruitment of young turtles to Australian foraging grounds has declined by 50 per cent over the last 20 years, approximately.470,2121 The proportion of first-time breeding female loggerheads within the annual nesting population on the Woongarra coast has declined from 41.5 per cent in 2001 to 20.9 per cent in 2021.438 The loggerhead population foraging in eastern Australian is already excessively biased to males in all age classes, and most juveniles successfully recruiting to foraging grounds are males. The island beaches produce relatively high proportions of male hatchlings, suggesting that the recruiting cohort predominantly originate from the islands and mainland hatchlings may be experiencing barriers to successful recruitment. Post-hatchling turtles from the mainland may be affected by changes to winds that could reduce their ability to move away from the nesting area and enter the East Australian Current to begin dispersal. However, research is required to confirm this. Similarly, ambient night-time light can disorient emerging hatchlings, causing them to go the wrong way or congregate around artificial structures where they are vulnerable to higher levels of predation.2122 The impact of artificial light on the Woongarra coast has been highlighted in recent years as coastal urban expansion continues near major mainland nesting sites. Low recruitment is expected to result in a decline in nesting once the current juvenile cohorts grow and reach maturity.

Despite the Region’s loggerhead population showing initial recovery in response to the local management actions, the population is facing a suite of continuing and increasing threats, many of which are unquantified. Existing management efforts, such as mandatory use of turtle excluder devices, predator control programs and beach cooling projects, including re-establishing the swamp behind Mon Repos beach, are considered essential to the long-term recovery and resilience of the stock.