12.

Boxshall, A. and Torok, S. 2024, The Rapid Assessment Workshops to elicit expert input to inform the development of the Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2024, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Townsville.

76.

Mandubarra Aboriginal Land and Sea Inc and Regional Advisory and Innovation Network (RAIN) Pty Ltd 2020, Mandubarra Sea Country cultural values: 2019-2020 mapping project, Mandubarra Aboriginal Land and Sea Inc.

78.

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority 2021, Woppaburra Traditional Owner heritage assessment (Document No. 100428), Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

142.

Scott, A.L., York, P.H. and Rasheed, M.A. 2021, Herbivory has a major influence on structure and condition of a Great Barrier Reef subtropical seagrass meadow, Estuaries and Coasts 44(2): 506-521.

263.

Flint, M., Brand, A., Bell, I.P. and Madden Hof, C.A. 2019, Monitoring the health of green turtles in northern Queensland post catastrophic events, Science of the Total Environment 660: 586-592.

438.

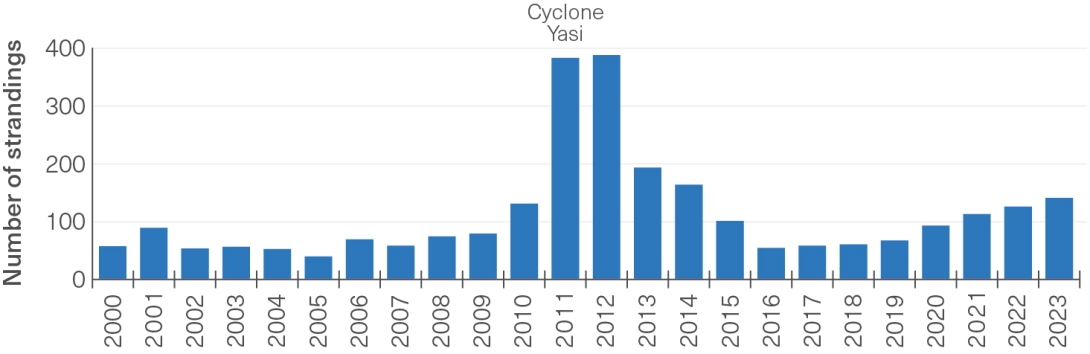

Department of Environment Science and Innovation 2023, Queensland turtle conservation project database. Unpublished report.

439.

Obura, D.O., Harvey, A., Young, T., Eltayeb, M.M. and Von Brandis, R. 2010, Hawksbill turtles as significant predators on hard coral, Coral Reefs 29(3): 759.

440.

Scott, A.L., York, P.H. and Rasheed, M.A. 2020, Green turtle (Chelonia mydas) grazing plot formation creates structural changes in a multi-species Great Barrier Reef seagrass meadow, Marine Environmental Research 162: 105183.

442.

Dabu Jajikal Aboriginal Corporation 2022, Balabay (Weary Bay) Heritage Management Implementation Plan.

443.

Department of Environment and Science 2021, Queensland Marine Turtle Conservation Strategy (2021-2031), Queensland Government, Brisbane.

444.

Department of Environment and Science 2018, Queensland Marine Turtle Conservation Strategy, Queensland Government, Brisbane.

445.

Laloë, J., Schofield, G. and Hays, G.C. 2024, Climate warming and sea turtle sex ratios across the globe, Global Change Biology 30(1): e17004.

446.

Booth, D.T., Dunstan, A., Bell, I., Reina, R. and Tedeschi, J. 2020, Low male production at the world’s largest green turtle rookery, Marine Ecology Progress Series 653: 181-190.

447.

Miller, J.D. and Limpus, C.J. 1981, Incubation period and sexual differentiation in the green turtle, Chelonia mydas, in eds. C. B. Banks and A. A. Martin, The Zoological Board of Victoria, Melbourne, pp. 66-73.

448.

Gammon, M., Bentley, B., Fossette, S. and Mitchell, N.J. 2024, Reconstructed and projected beach temperatures reveal where flatback turtles are most at risk from climate change, Global Ecology and Conservation 51: e02866.

449.

Staines, M.N., Booth, D.T., Madden Hof, C.A. and Hays, G.C. 2020, Impact of heavy rainfall events and shading on the temperature of sea turtle nests, Marine Biology 167(12): 190.

450.

Smith, C.E., Booth, D.T., Crosby, A., Miller, J.D., Staines, M.N., et al. 2021, Trialling seawater irrigation to combat the high nest temperature feminisation of green turtle, Chelonia mydas, hatchlings, Marine Ecology Progress Series 667: 177-190.

451.

Pillans, R.D., Fry, G.C., Haywood, M.D.E., Rochester, W., Limpus, C.J., et al. 2021, Residency, home range and tidal habitat use of Green Turtles (Chelonia mydas) in Port Curtis, Australia, Marine Biology 168(6): 88.

452.

Hamann, M., Shimada, T., Duce, S., Foster, A., To, A.T.Y., et al. 2022, Patterns of nesting behaviour and nesting success for green turtles at Raine Island, Australia, Endangered Species Research 47: 217-229.

453.

Vijayasarathy, S., Baduel, C., Hof, C., Bell, I., Ramos, M.D.M.G., et al. 2019, Multi-residue screening of non-polar hazardous chemicals in green turtle blood from different foraging regions of the Great Barrier Reef, Science of the Total Environment 652: 862-868.

454.

Weltmeyer, A., Dogruer, G., Hollert, H., Ouellet, J.D., Townsend, K., et al. 2021, Distribution and toxicity of persistent organic pollutants and methoxylated polybrominated diphenylethers in different tissues of the green turtle Chelonia mydas, Environmental Pollution 277: 116795.

455.

Flint, M., Eden, P.A., Limpus, C.J., Owen, H., Gaus, C., et al. 2015, Clinical and pathological findings in green turtles (Chelonia mydas) from Gladstone, Queensland: investigations of a stranding epidemic, EcoHealth 12: 298-309.

456.

Limpus, C.J., Miller, J.D., Parmenter, C.J. and Limpus, D.J. 2003, The green turtle, Chelonia mydas, population of Raine Island and the northern Great Barrier Reef: 1843-2001, Memoirs-Queensland Museum 49(1): 349-440.

457.

Limpus, C.J. 2008, A biological review of Australian marine turtle species, 2. Green turtle, Chelonia mydas (Linnaeus), Environmental Protection Agency, Brisbane.

458.

Coffee, O. and Robertson, K. 2022, Raine Island Recovery Project 2021-22 Technical Report to the Raine Island Scientific Advisory Committee and Raine Island Reference Group, Queensland Government, Brisbane.

459.

Coffee, O. and Robertson, K. 2021, Raine Island Recovery Project: 2020-2021 Season technical report to the Raine Island Scientific Advisory Committee and Raine Island Reference Group, Department of Environment and Science, Brisbane.

460.

Booth, D.T., Dunstan, A., Robertson, K., Tedeschi, J. and Deakin, J. 2021, Egg viability of green turtles nesting on Raine Island, the world’s largest nesting aggregation of green turtles, Australian Journal of Zoology 69(1): 12-17.

461.

Department of Environment Science and Innovation 2024, 'StrandNet Database'. Unpublished report.

462.

Bell, I.P., Meager, J.J., Eguchi, T., Dobbs, K.A., Miller, J.D., et al. 2020, Twenty-eight years of decline: nesting population demographics and trajectory of the north-east Queensland endangered hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), Biological Conservation 241: 108376.

463.

Bell, I. and Jensen, M.P. 2018, Multinational genetic connectivity identified in western Pacific hawksbill turtles, Eretmochelys imbricata, Wildlife Research 45(4): 307-315.

464.

Barr, C.E., Hamann, M., Shimada, T., Bell, I., Limpus, C.J., et al. 2021, Post-nesting movements and feeding ground distribution by the hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) from rookeries in the Torres Strait, Wildlife Research 48(7): 598-608.

465.

Hamilton, R.J., Desbiens, A., Pita, J., Brown, C.J., Vuto, S., et al. 2021, Satellite tracking improves conservation outcomes for nesting hawksbill turtles in Solomon Islands, Biological Conservation 261: 109240.

466.

Madden Hof, C.A., Smith, C., Miller, S., Ashman, K., Townsend, K.A., et al. 2023, Delineating spatial use combined with threat assessment to aid critical recovery of northeast Australia’s endangered hawksbill turtle, one of western Pacific's last strongholds, Frontiers in Marine Science 10.

467.

Perez, M.A., Limpus, C.J., Hofmeister, K., Shimada, T., Strydom, A., et al. 2022, Satellite tagging and flipper tag recoveries reveal migration patterns and foraging distribution of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) from eastern Australia, Marine Biology 169(6): 80.

468.

Donnelly, A.P., Muñoz-Pérez, J.P., Jones, J. and Townsend, K.A. 2020, Turtles in trouble: the argument for sea turtles as flagship species to catalyse action to tackle marine plastic pollution: case studies of cross sector partnerships from Australia and Galapagos, Br.Chelonia Group 9: 14.

469.

Limpus, C.J. 2009, A Biological Review of Australian Marine Turtles, Environmental Protection Agency, Brisbane.

470.

Limpus, C.J., Anderson, D., Debets, K., Ferguson, J., Fien, L., et al. 2022, Queensland turtle conservation project: data report for marine turtle breeding on the Woongarra coast, 2021-2022 breeding season, Department of Environment and Science, Queensland Government, Brisbane.

471.

McLachlan, N., McLachlan, B. and Limpus, C.J. 2023, Data report for marine turtle breeding on the Wreck Rock coast, 2022-2023 breeding season, Conservation Technical and Data Report 2023 (1):1-24.

472.

FitzSimmons, N.N., Pittard, S.D., McIntyre, N., Jensen, M.P., Guinea, M., et al. 2020, Phylogeography, genetic stocks, and conservation implications for an Australian endemic marine turtle, Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 30(3): 440-460.

473.

Limpus, C.J., Chaloupka, M., Ferguson, J., FitzSimmons, N.N. and Parmenter, C.J. 2020, The Flatback turtle, Natator depressus, in Queensland: population size and trends, Department of Environment and Science, Brisbane.

474.

Limpus, C.J., FitzSimmons, N.N., Anderson, I., Bennett, W., Baldwin, L., et al. 2021, Monitoring of eastern Australian flatback turtle, Natator depressus, breeding populations in the Gladstone region: 2020-2021 breeding season, Department of Environment and Science, Queensland Government, Brisbane.

475.

ABC News 2021, Leatherback turtle sightings could indicate return to Queensland shores to nest.

-