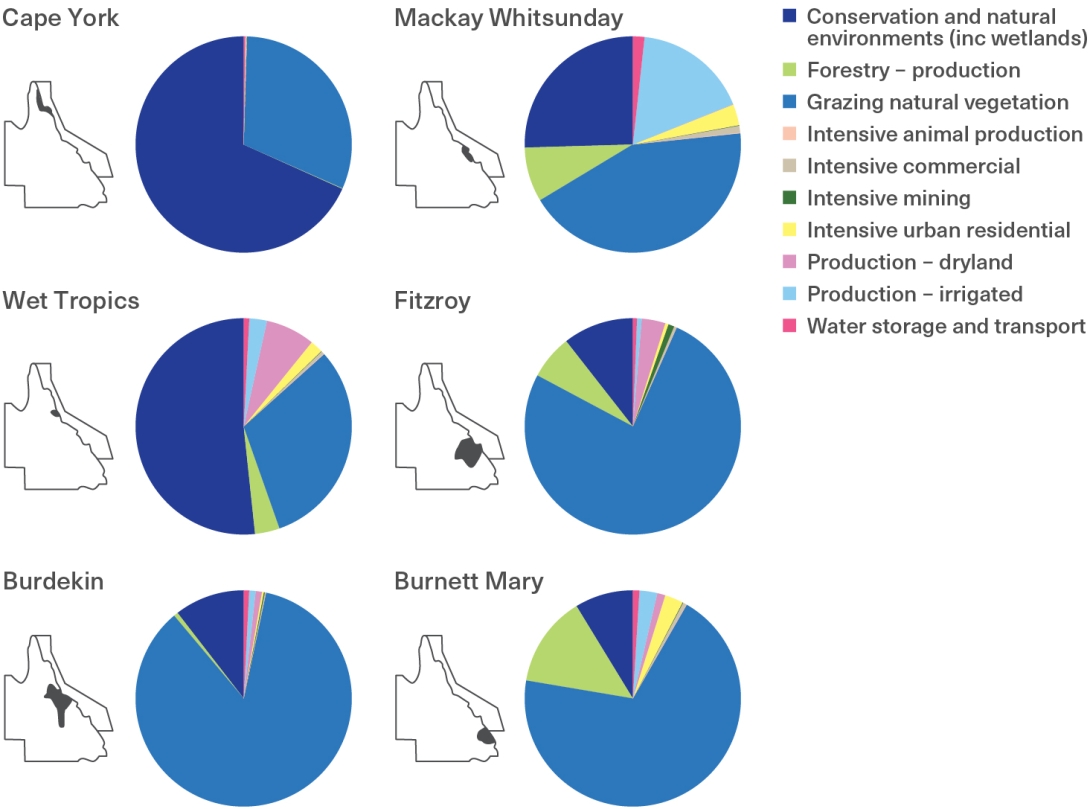

The catchments, coastline and islands of the Region are human landscapes, accommodating approximately 1.2 million people and a range of different activities and land use practices (Figure 6.9). Coastal development includes all development activities, construction and land uses in the Catchment, coastlines and islands. Since the arrival of Europeans in the Region in the mid-1800s, broadscale changes have occurred in land use, resulting in widespread changes in landscapes. These historical changes, along with current activities, affect Reef ecosystems.1734

Figure 6.9

Proportion of land uses in the Catchment by natural resource management region

Catchment land uses are grouped according to similarities in the ecological functions they provide to the Reef. The graphs (right) present the data captured in 2021 for each natural resource management region (left) in the Great Barrier Reef Catchment. Source: Adapted from Queensland Department of Environment, Science and Innovation (2023)1735

Coastal development in the Region is driven by a range of factors, with major land use changes in the Catchment over the past 150 years linked to national and state development schemes and global market forces,332 as well as the needs of the local population. Population growth drives coastal development, particularly in urban areas, intensifying infrastructure demands; for example, more roads and larger stormwater networks, more sewage treatment, increased food production and expansion into previously remote areas of the Catchment. Proposed infrastructure plans for Queensland now include renewable energy zones within the Catchment,1736 upgrading infrastructure to encourage major energy projects such as large-scale wind, solar and hydrogen power stations, as well as the world’s largest pumped storage hydropower scheme which is proposed across the Pioneer Valley and Burdekin Basin catchments.1509 Overall, a range of the land uses that can significantly impact the Reef's condition are at, or close to, historical highs of landcover and production, including cattle, cropping and aquaculture.