The Reef is enjoyed recreationally by Queensland’s coastal communities,1369 by other Australians 1370 and by the broader international community. Aside from commercial operations and tourism, people use the Region for a wide range of recreational activities, including relaxation, stress reduction through access to natural settings, and enjoyment through snorkelling, boating and diving. Recreational fishing, a major part of recreational activities, is considered in Section 5.4.

Quantifying and monitoring recreational use of the Reef in terms of numbers of people and locations is difficult and gaps remain in our understanding of trends. It is especially hard to distinguish recreation other than fishing from reported statistics that often include recreational fishing and sometimes tourism.

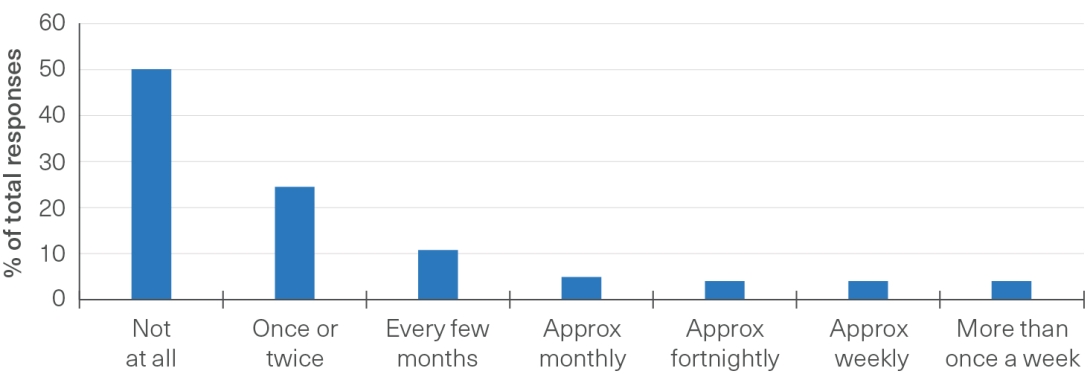

In a 2021 survey, 82 per cent of Region residents had visited the Reef at least once in their lifetime and 50 per cent had visited the Reef once in the previous 12 months for recreation.1075 Most residents (35.5 per cent) visit only once, twice or every few months. A smaller proportion (14 per cent) make more regular visits, either monthly, fortnightly, weekly or more than once a week (Figure 5.12).1075 Slightly more than 50 per cent of the residents who had already visited the Reef once in their lifetime reported that they would choose to visit the Reef over other places in their recreational time.1075 Residents place a high value on the socialising and lifestyle benefits provided by the Reef.1075 The most popular recreation activities in and around regional waterways include swimming, picnics and barbecues, wildlife watching and nature appreciation, exercising and fishing (recreational fishing is addressed in Section 5.4).1159