5.

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority 2019, Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2019, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Townsville.

327.

Johnston, D., Chandrapavan, A., Walton, L., Beckmann, C., Johnson, D., et al. 2021, Blue Swimmer Crab Portunus armatus in Status of Australian fish stocks reports, Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

328.

Saunders, T., Johnson, D., Johnston, D. and Walton, L. 2021, Mud Crabs Scylla spp., Scylla serrata, Scylla olivacea in Status of Australian fish stocks reports, Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

420.

Usher, M., Braccini, M., Peddemors, V. and Roelofs, A. 2021, Common Blacktip Shark - Carcharhinus limbatus, in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, P. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

421.

Usher, M., Braccini, M., Roelofs, A. and Peddemors, V. 2021, Australian Blacktip Shark - Carcharhinus tilstoni, in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, O. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

422.

Usher, M., Braccini, M. and Roelofs, A. 2021, Spot-Tail Shark - Carcharhinus sorrah, in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, P. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

793.

French, S.M. 2023, Stock Assessment of Ballot's saucer scallop (Ylistrum balloti) in Queensland, Australia, with data to October 2022, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

794.

Kangas, M. and Roelofs, A. 2021, Ballot's Saucer Scallop - Ylistrum balloti, in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, P. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

1221.

Teixeira, D., Janes, R. and Webley, J. 2020, 2019-20 statewide recreational fishing survey, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1222.

Taylor, S., Webley, J. and McInnes, K. 2012, 2010 Statewide Recreational Fishing Survey, Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Brisbane.

1223.

Webley, J., McInnes, K., Teixeira, D., Lawson, A. and Quinn, R. 2015, Statewide recreational fishing survey 2013-14, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1224.

Department of Agriculture and Fisheries 2023, Queensland Boat Ramp Surveys Dashboard, Queensland Government.

1225.

Department of Agriculture and Fisheries 2023, Queensland Recreational Fishing Surveys Dashboard, Queensland Government.

1226.

State of Queensland 2018, Charter fishing action plan 2018-2021.

-

1228.

Department of Agriculture and Fisheries 2023, Management advice Reef line fishery 2023, State of Queensland.

1229.

Department of Agriculture and Fisheries 2020, Queensland AgTrends 2020-21: Forecasts and trends in Queensland agricultural, fisheries and forestry production, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

-

1231.

Grech, A. and Coles, R. 2011, Interactions between a trawl fishery and spatial closures for biodiversity conservation in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area, Australia, PLoS ONE 6(6): e21094.

1232.

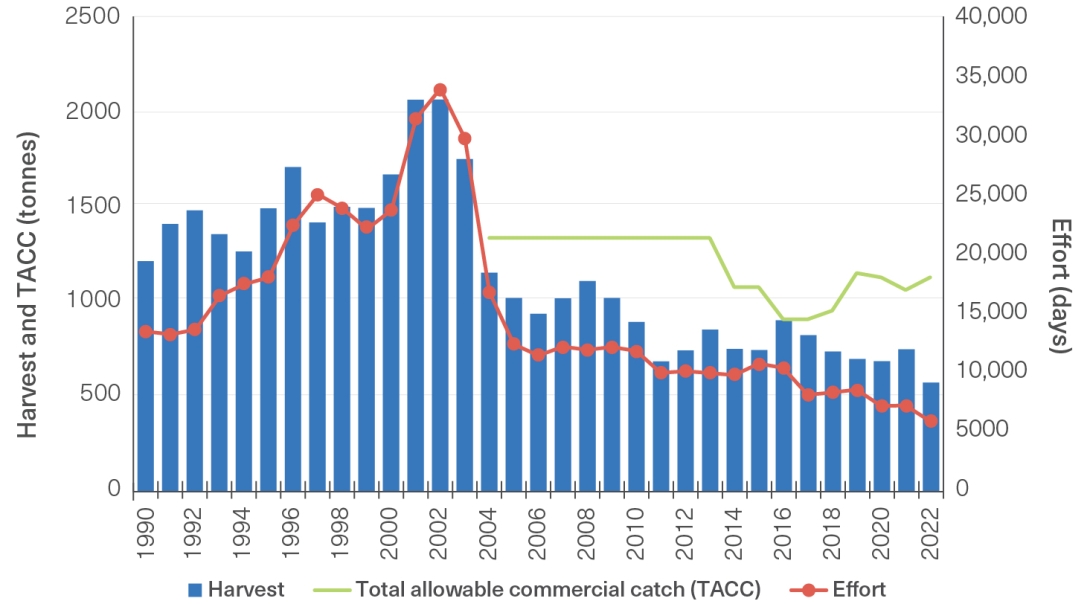

State of Queensland 2021, Trawl fishery (northern region) Harvest Strategy: 2021–2026, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.

1233.

State of Queensland 2021, Trawl fishery (central region) Harvest Strategy: 2021–2026, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.

1234.

State of Queensland 2021, Trawl fishery (southern inshore region) Harvest Strategy: 2021–2026, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.

1235.

State of Queensland 2021, Trawl fishery (southern offshore A and B regions) Harvest Strategy: 2021–2026, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.

1236.

State of Queensland 2021, Trawl fishery (Moreton Bay region) Harvest Strategy: 2021–2026, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.

1237.

Dedini, E. and Jacobsen, I. 2023, East Coast Otter Trawl Fishery Scoping Study, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1238.

Pitcher, C.R., Rochester, W., Dunning, M., Courtney, T., Broadhurst, M., et al. 2018, Putting potential environmental risk of Australia's trawl fisheries in landscape perspective: exposure of seabed assemblages to trawling, and inclusion in closures and reserves, FRDC Project No 2016-039, CSIRO Oceans & Atmosphere, Brisbane.

1239.

McMillan, M.N., Brunjes, N., Williams, S.M. and Holmes, B.J. 2024, Broad-scale genetic population connectivity in the Moreton Bay Bug (Thenus australiensis) on Australia’s east coast, Hydrobiologia 851(10): 2347-2355.

1240.

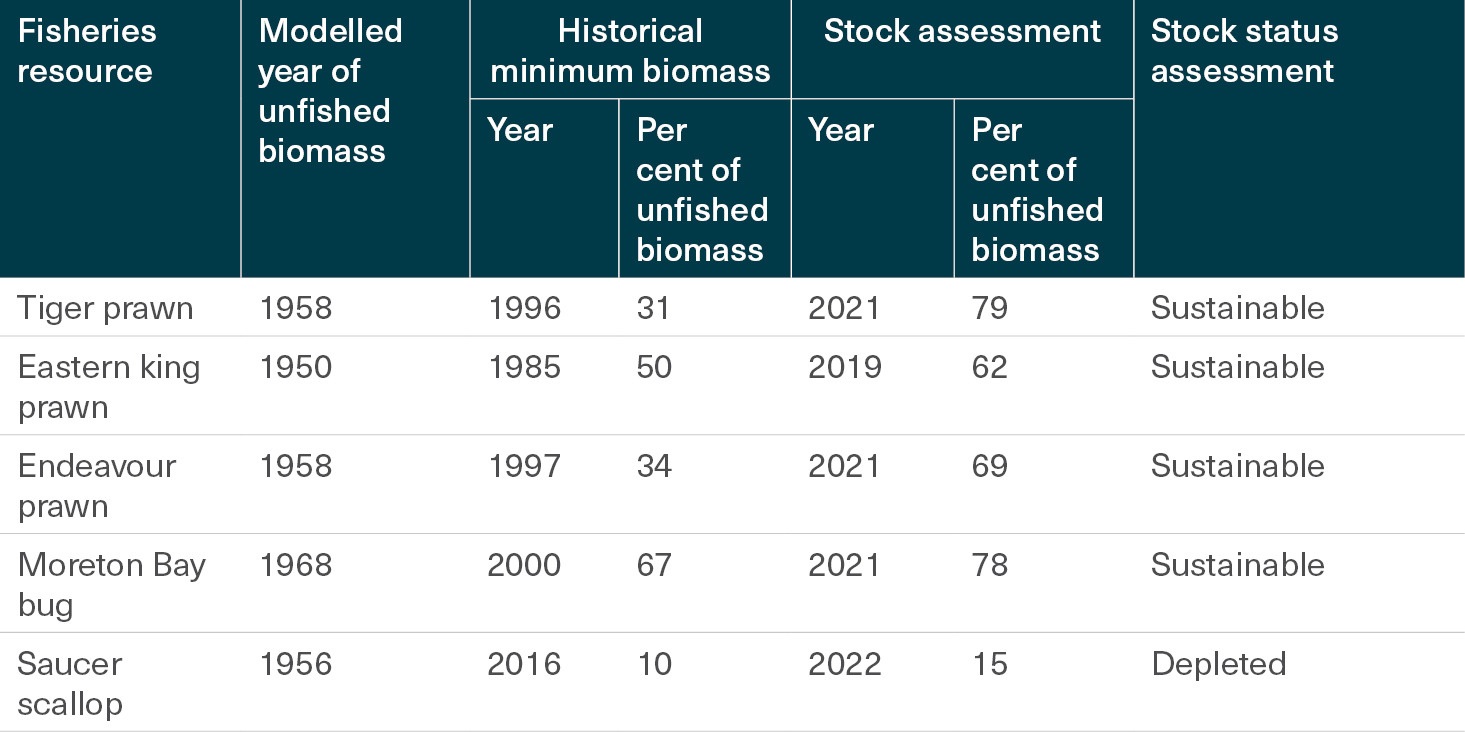

Lovett, R.A., Fox, A.R., Wickens, M.E. and Hillcoat, K.B. 2023, Stock assessment of Queensland east coast tiger prawns (Penaeus esculentus and Penaeus semisulcatus), Australia, with data to December 2021, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1241.

Helidoniotis, F., O'Neill, M.F. and Taylor, M. 2020, Stock assessment of eastern king prawn (Melicertus plebejus), State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1242.

Fox, A.R., Lovett, R.A., Wickens, M.E. and Hillcoat, K.B. 2023, Stock assessment of Queensland east coast red spot king prawns (Melicertus longistylus), Australia, with data to December 2021, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1243.

Fox, A.R., Lovett, R.A., Wickens, M.E. and Hillcoat, K.B. 2023, Stock assessment of Queensland east coast endeavour prawns (Metapenaeus endeavouri and Metapenaeus ensis), Australia, with data to December 2021, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1244.

Wickens, M.E., Hillcoat, K.B., Lovett, R.A., Fox, A.R. and McMillan, M.N. 2023, Stock assessment of Moreton Bay bugs (Thenus australiensis and Thenus parindicus) in Queensland, Australia with data to December 2021, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1245.

Roelofs, A., Larcombe, J., Kangas, M. and Zeller, B. 2021, Moreton Bay Bugs Thenus parindicus, Thenus australiensis, Thenus spp. in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, P. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

1246.

Roelofs, A., Butler, I. and Kangas, M. 2021, Endeavour Prawns - Metapenaeus endeavouri, Metapenaeus ensis, in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, P. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

1247.

Roelofs, A., Kangas, M., Butler, I. and Saunders, T. 2021, Redspot King Prawn Melicertus longistylus, in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, P. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

1248.

Roelofs, A. and Taylor, M. 2021, Eastern King Prawn - Melicertus plebejus, in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, P. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

1249.

Butler, I., Kangas, M., Roelofs, A., Taylor, M. and Zeller, B. 2021, Tiger Prawns - Penaeus esculentus, Penaeus semisulcatus, in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, P. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

1250.

Commonwealth of Australia 2021, Assessment of the Queensland East Coast Otter Trawl Fishery.

1251.

Department of Agriculture and Fisheries 2017, Queensland Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1252.

Queensland Government 2021, Fisheries (Saucer Scallops) Amendment Declaration 2021.

1253.

State of Queensland 2021, East coast inshore fishery harvest strategy: 2021–2026, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brisbane.

1254.

Leigh, G.M., Janes, R., Williams, S.M. and Martin, T. 2022, Stock Assessment of Queensland East Coast black jewfish (Protonibea diacanthus), Australia, with data to December 2021, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1255.

Saunders, T., Pidd, A., Trinnie, F. and Newman, S. 2021, Black Jewfish - Protonibea diacanthus, in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, P. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

1256.

Tanimoto, M., Fox, A.R., O'Neill, M.F. and Langstreth, J.C. 2021, Stock assessment of Australian east coast Spanish mackerel (Scomberomorus commerson), State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1257.

Roelofs, A., Langstreth, J., Lewis, P., Butler, I., Stewart, J. and Grubert, M. 2021, Spanish Mackerel Scomberomorus commerson, in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, P. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

1258.

State of Queensland 2022, East coast Spanish mackerel fishery harvest strategy 2023–2028, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.

1259.

Department of Agriculture and Fisheries 2019, Rocky Reef Fin Fish Fishery Scoping Study, State of Queensland.

1260.

Wortman, J. 2020, Queensland rocky reef finfish harvest and catch rates July 2020, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1261.

Fowler, A., Stewart, J., Victorian Fisheries Authority, Roelofs, A., Garland, A. and Jackson, G. 2021, Snapper Chrysophrys auratus, in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, P. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

1262.

Walton, L. and Jacobsen, I. 2021, Rocky Reef Fishery Level 2 Ecological Risk Assessment, State of Queensland.

1263.

Wortmann, J., O'Neill, M.F., Sumpton, W., Campbell, M.J. and Stewart, J. 2018, Stock assessment of Australian east coast snapper (Chrysophrys auratus) Predictions of stock status and reference points for 2016, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1264.

Roelofs, A. and Stewart, J. 2021, Pearl Pearch Glaucoma scapulare, in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, P. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

1265.

Lovett, R., Northrop, A. and Stewart, J. 2022, Stock assessment of Australian pearl perch (Glaucosoma scapulare) with data to December 2019, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1266.

Filar, J.A., Courtney, A.J., Gibson, L.J., Jemison, R., Leahy, S.M., et al. 2021, Modelling environmental changes and effects on wild-caught species in Queensland. Environmental drivers., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Brisbane.

1267.

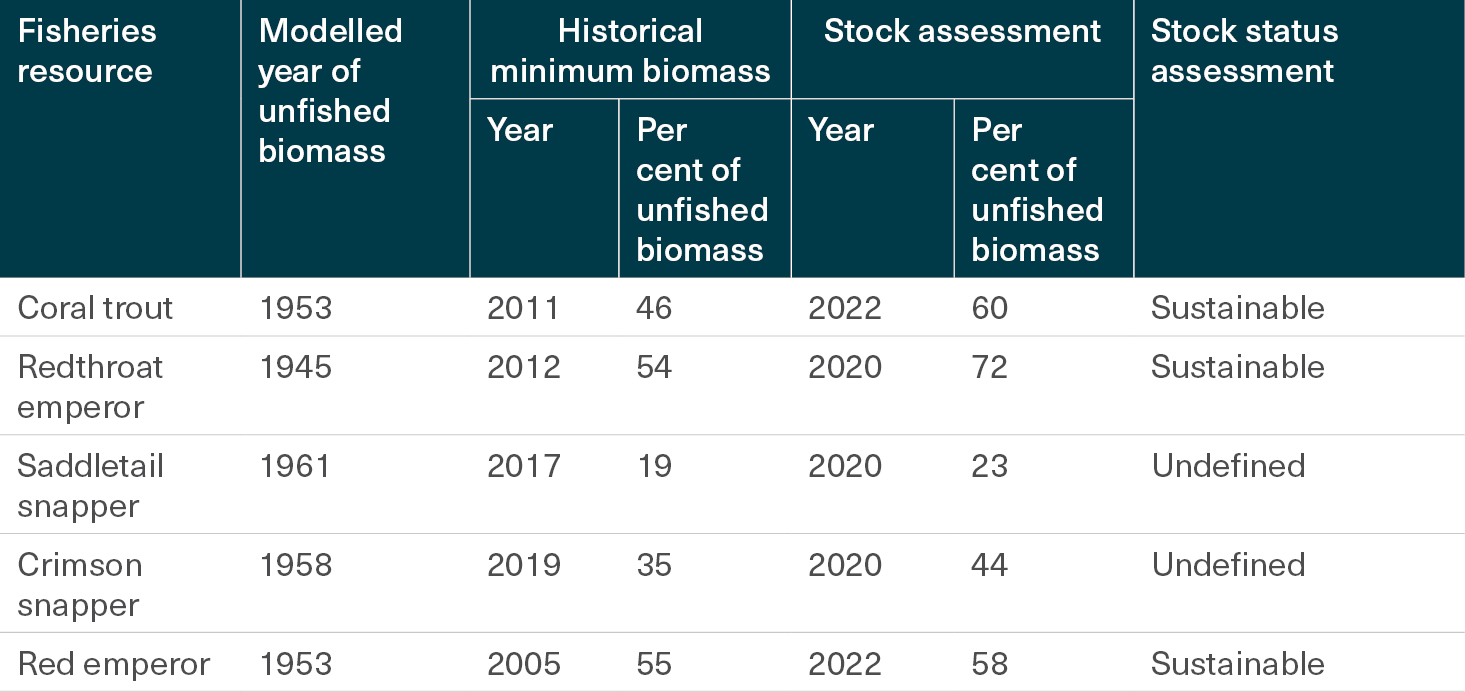

Jacobsen, I., Dawson, A. and Walton, L. 2019, Coral Reef Fin Fish Fishery Scoping Study, State of Queensland.

1268.

BDO EconSearch 2023, Economic and Social Indicators for Queensland’s Commercial Fisheries in 2020/21: A Report for Fisheries Queensland, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brisbane.

1269.

Saunders, T., Roelofs, A., Butler, I., Trinnie, F. and Newman, S. 2021, Coral trouts Plectropomus spp. & Variola spp., in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, P. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

1270.

Fox, A.R., Campbell, A.B. and Sieth, J.D. 2022, Stock assessment of Queensland east coast common coral trout (Plectropomus leopardus), Australia, with data to December 2021, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1271.

Department of Agriculture and Fisheries 2022, Reef line fisher working group communiques - Communique 17-18 March 2022, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1272.

Saunders, T., Roelofs, A. and Fairclough, D. 2021, Red Throat Emperor Lethrinus miniatus, in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, P. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

1273.

Northrop, A.R. and Campbell, A.B. 2020, Stock assessment of the Queensland east coast redthroat emperor (Lethrinus miniatus), State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1274.

Sumpter, L.I., Fox, A.R. and Hillcoat, K.B. 2022, Stock assessment of Queensland east coast red emperor (Lutjanus sebae), Australia, with data to June 2021, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1275.

Fox, A.R., Campbell, A.B., Sumpter, L. and Hillcoat, K.B. 2021, Stock assessment of Queensland east coast crimson snapper (Lutjanus erythropterus), Australia, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1276.

Campbell, A.B., Fox, A.R., Hillcoat, K.B. and Sumpter, L. 2021, Stock assessment of Queensland east coast saddletail snapper (Lutjanus malabaricus), Australia, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1277.

Piddocke, T., Crispian, A., Hartmann, K., Hesp, A., Hone, P., Klemke, J., Mayfield, S., Roelofs, A., Saunders, T., Steward, J., Wise, B. and Woodhams, J. (eds) 2021, Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

1278.

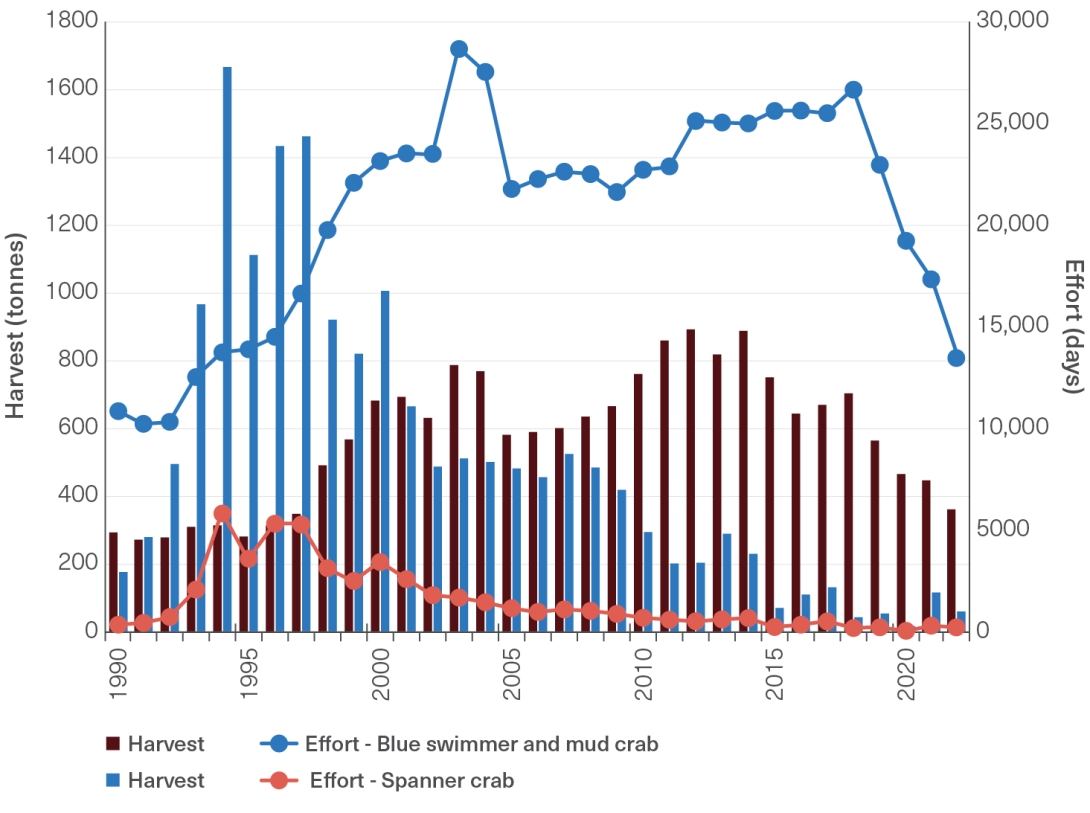

State of Queensland 2021, Queensland Spanner Crab Harvest Strategy: 2020–2025, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brisbane.

1279.

State of Queensland 2021, Queensland Blue Swimmer Harvest Strategy: 2021–2026, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brisbane.

1280.

State of Queensland 2021, Queensland Mud Crab Fishery Harvest Strategy: 2021–2026, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brisbane.

1281.

Roelofs, A., Johnson, D. and McGilvray, J. 2021, Spanner Crab Ranina ranina, in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, P. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

1282.

Lovett, R.A., O'Neill, M.F. and Garland, A. 2020, Stock assessment of Queensland east coast blue swimmer crab (Portunus armatus), State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1283.

Commonwealth of Australia 2021, Approved Wildlife Trade Operation Declarations (Queensland Blue Swimmer Crab Fishery and Queensland Mud Crab Fishery) Revocation Instrument, December 2021, Brisbane.

1284.

O'Neill, M.F., Campbell, A.B. and McGilvray, J.G. 2022, Total allowable commercial catch review for Queensland spanner crab (Ranina ranina), with data to December 2021, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

-

1286.

Walton, L. and Jacobsen, I. 2020, Crab Fishery Level 2 Ecological Risk Assessment, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1287.

State of Queensland 2021, Queensland sea cucumber fishery harvest strategy: 2021–2026, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brisbane.

1288.

Helidoniotis, F. 2021, Stock assessment of white teatfish (Holothuria fuscogilva) in Queensland, Australia, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1289.

Roelofs, A., Butler, I. and Grubert, M. 2021, White teatfish (Sea Cucumber), in Status of Australian fish stocks reports 2020, eds T. Piddcocke, C. Ashby, K. Hartmann, A. Hesp, P. Hone, et al., Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra.

1290.

Commonwealth of Australia 2021, Assessment of the Queensland Sea Cucumber Fishery (East Coast), Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment, Canberra.

1291.

Morton, J. and Jacobsen, I. 2022, Queensland Coral Fishery Scoping Study, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1292.

Morton, J., Jacobsen, I. and Dedini, E. 2022, Queensland Coral Fishery Ecological Risk Assessment Update [Phase 1], State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1293.

State of Queensland 2021, Marine Aquarium Fish Harvest Strategy: 2021–2026, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brisbane.

1294.

Commonwealth of Australia 2023, Declaration of an approved Wildlife Trade Operation – Queensland Aquarium Fish Fishery, November 2023, Department of Climate Change Energy Environment and Water, Canberra.

1295.

Department of Agriculture and Fisheries 2023, Marine Aquarium Fish Fishery Scoping Study, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1296.

Morton, J. and Jacobsen, I. 2023, Marine Aquarium Fish Fishery Level 1 Ecological Risk Assessment, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1297.

State of Queensland 2021, Queensland Tropical Rock Lobster Harvest Strategy: 2021–2026, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brisbane.

1298.

Plagányi, É, Deng, R.A., Tonks, M., Murphy, N., Pascoe, S., et al. 2021, Indirect Impacts of COVID-19 on a tropical lobster fishery’s harvest strategy and supply chain, Frontiers in Marine Science 8(686065).

1299.

Department of Agriculture and Fisheries 2023, Queensland Shark Control Program catch statistics for Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, State of Queensland, Brisbane.

1300.

Commonwealth of Australia and State of Queensland 2015, Great Barrier Reef Intergovernmental Agreement, Commonwealth of Australia and State of Queensland, Canberra and Brisbane.

-

-

1303.

Department of the Environment and Water Resources 2007, Guidelines for the ecologically sustainable management of fisheries, 2nd Edition, Australian Government.

1304.

Queensland Government 2019, Fact Sheet: Changes to fishing rules in Queensland September 2019 - Fish for the future, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brisbane.

1305.

Queensland Government 2019, Fact Sheet: Changes to fishing rules in Queensland September 2019 - Recreational, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brisbane.

1306.

Queensland Government 2019, Fact Sheet: Changes to fishing rules in Queensland September 2019 - Commercial, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brisbane.

1307.

Queensland Government 2020, Fact Sheet: Changes to fishing rules in Queensland September 2020 - Fish for the future, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brisbane.

-

1309.

Queensland Government 2020, Fact Sheet: Crab fishery quota allocation, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brisbane.

1310.

Queensland Government 2020, East Coast Inshore Fishery quota allocation, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brisbane.

1311.

Queensland Government 2020, Trawl fishery effort unit allocation, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Brisbane.

-

-

-

-