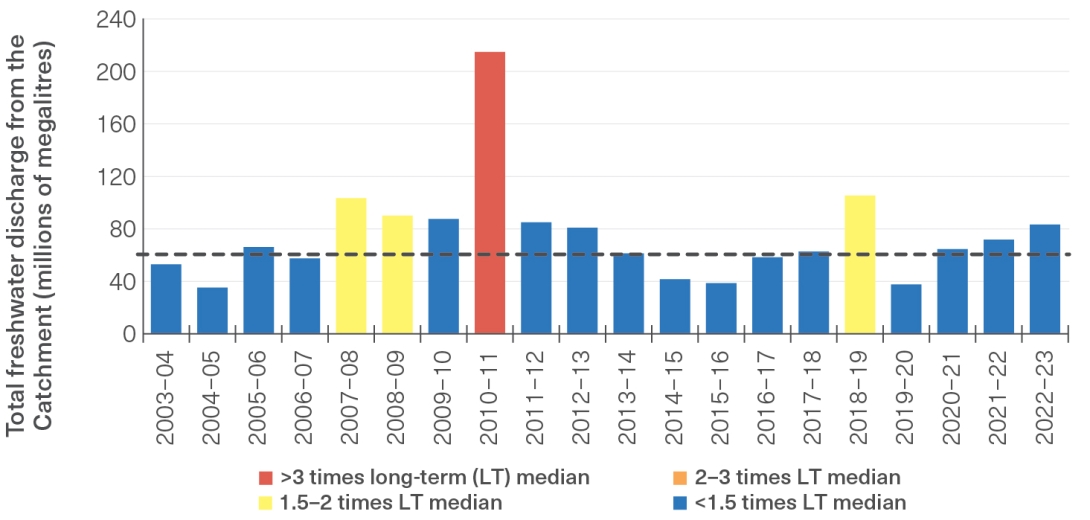

The Reef receives freshwater inflow from a Catchment area of approximately 424,000 square kilometres, about a quarter the area of Queensland.42 These flows are driven by rainfall patterns that are highly variable on seasonal, inter-annual and decadal timescales. Sixty to 80 per cent of rainfall occurs during the wet season (December to April), often associated with monsoon troughs and the passage of low-pressure systems and cyclones.568 More extremes in flow are being experienced during wet and dry seasons. Variation from year to year is strongly linked to major climatic drivers, such as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation and the Madden–Julian Oscillation (Box 6.1). Monsoonal and cyclonic events can cause major flooding across the Region. These varied temporal patterns are superimposed on decadal rainfall trends occurring due to climate change.

Rainfall in northern Queensland has increased by around 10 per cent since 1750 and has become more variable, as rainy years became much wetter, while dry years remained dry.569 Heavy rainfall events are predicted to become less frequent but more intense as a result of ongoing global warming.540 Daily rainfall totals associated with thunderstorms have increased since 1979, particularly in northern Australia, but declined in other areas of the Great Barrier Reef Catchment. This trend is expected to continue in future.540

Following rainfall, major river systems transport vast amounts of freshwater runoff from the surrounding landscape, channelling it towards the coast and into the Reef. In many areas along the coast, fresh water is also channelled through extensive networks of wetlands and other coastal ecosystems.36 These act as natural filters and buffers, trapping and removing nutrients (including via denitrification) and sediment before they reach the ocean. Large flood events cause rivers to break their banks and inundate floodplains and wetlands, which affects the dissolved and suspended constituents of water entering the Reef. Historical clearing and draining of coastal wetlands are important legacy impacts affecting the quantity and quality of freshwater inflow.42

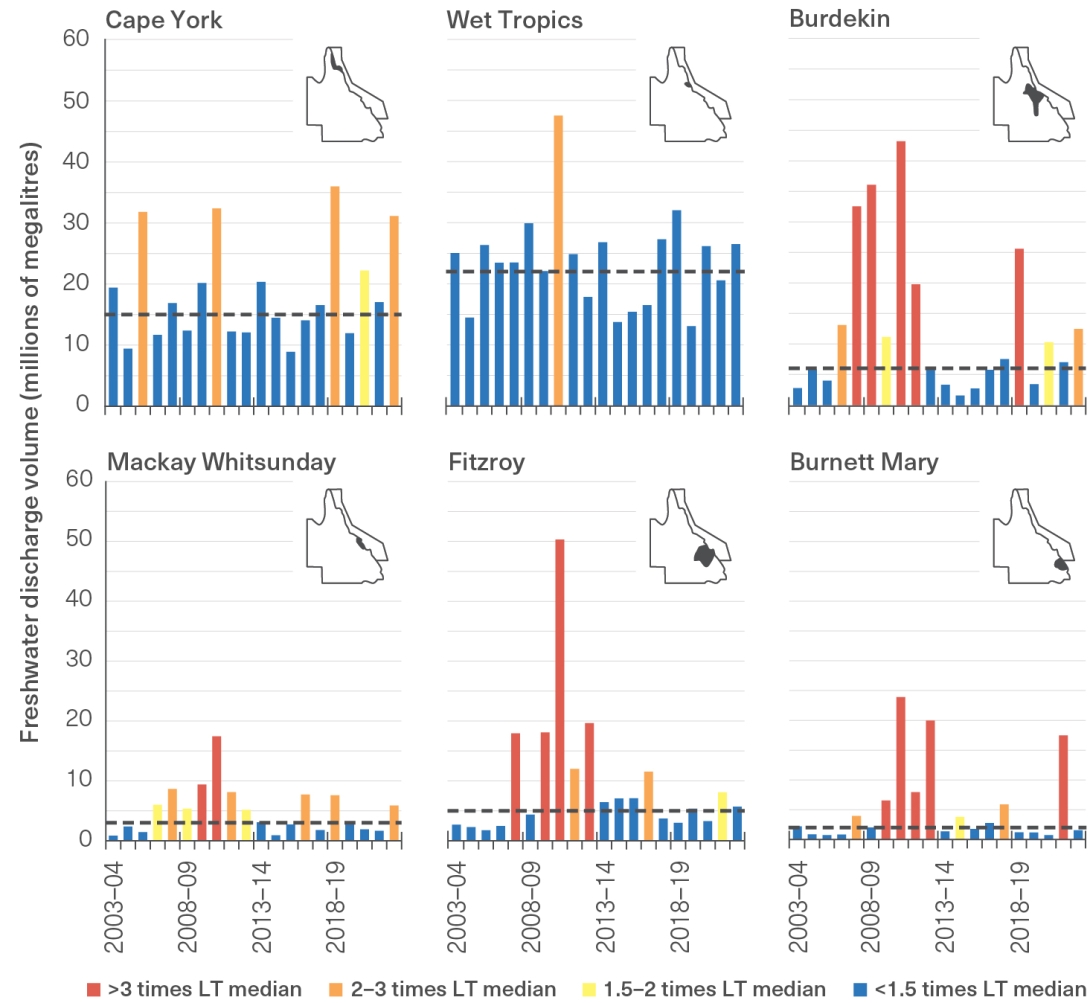

The Catchment is made up of 35 major river basins, which vary considerably in their volumes and patterns of discharge. Rivers in the Wet Tropics Natural Resource Management region generally flow year-round; their discharge is driven by groundwater base flow and higher, more consistent rainfall than in other regions. Average rainfall is also relatively high across parts of the Cape York and Mackay Whitsunday regions. Rivers in the Burdekin, Fitzroy and Burnett Mary regions exhibit highly variable discharge that is characterised by very large but infrequent flood events.

The most direct effect of freshwater inflow is a reduction in salinity, to which corals are sensitive.570 Fresh water is less dense than sea water, and it forms surface plumes that extend long distances in calm conditions. Freshwater inflow can also bring with it a range of land-sourced substances, including dissolved and particulate nutrients, suspended fine sediments, pesticides, and plastic waste (Section 6.5). In excess, many of the constituents of land-based runoff act as pollutants and can negatively affect organisms in nearshore waters. For example, land-sourced nutrients drive productivity in the marine environment but excess nutrients can be damaging to ecosystems.571 The combined effects of lower salinity, reduced light due to the suspended sediments, and high sedimentation can contribute to localised coral and seagrass mortality.572 At a Region-wide scale, exposure to floodwaters has been shown to correlate with declines in the recovery rate of coral cover.573